Lines

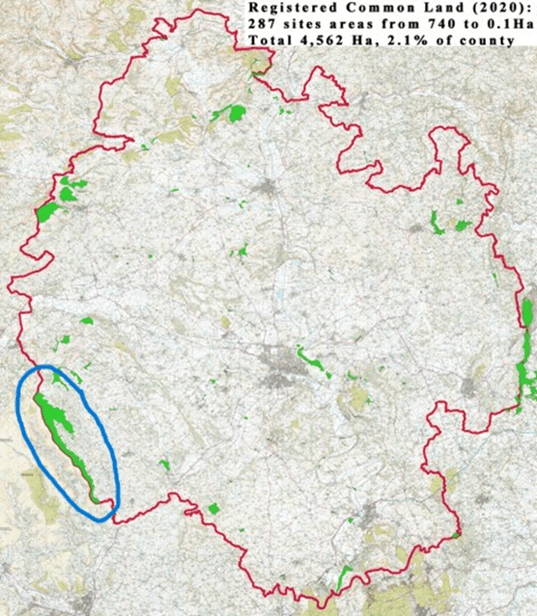

The common I’m walking on is the northern part of the upland commons along the Wales/ Herefordshire border, above the Olchon Valley, encompassing the popular Cats Back ridge walk. It’s part of a series of continuous commons, circled in blue on the left-hand map below, each with its own register of commoners. From the walker’s viewpoint it’s a seamless area and it adjoins commons on the Wales side of the Hatterall ridge so it’s part of the vast Black Mountains commons.

(thanks to David Lovelace for this county base map.)

Lines bisecting open spaces

We now associate commons with openness and unbounded access though of course their history encompasses land enclosures, dispossession and lots of demarcation, definition and line-drawing for the purpose of rules, limitations and specificities of land use that have changed over time. Major social changes have been caused by imposition/introduction of lines onto the landscape.

The uplifting, expansive experience of wandering – above hedges or fences – high up on open-access ground with big views, links to a concept of poetic freedom from boundaries, segmentation, order.

Today I want the sky,

The tops of the high hills,

Above the last man's house,

His hedges, and his cows,

Where, if I will, I look

Down even on sheep and rook……

(Edward Thomas, ‘The Lofty Sky’, 1915)

But actually many linear features I notice, walk along and cross over do draw my attention.

There are the geo-political lines – invisible on the ground (well, sometimes surviving old boundary stones can be spotted) though prominent on maps – such as political/administrative boundaries (nation, county, parish, diocese) or boundaries of ownership and commons rights areas. There’s the watershed line, a drawn line on some geological maps but not that clearcut on the ridge or valley top itself. There’s the sheep-hefting line within which a flock should stay when grazing the commons;.

The sheep don’t read the commons registration documents * which show where their owners’ rights officially start and finish. But sheep do have an innate awareness, learned from the flock’s matriarchs, where their hefted area is. (* Or do they?)

I was a bit surprised how many visible lines I stopped to ponder within the commons landscape. The ridgeline against the sky is a big presence viewed from below. Tracks made by humans, sheep, ponies or a combination, sometimes stand out and sometimes don’t, depending on the lie of the land, the vegetation or the angle of the light.

In this border area many landscape features have Welsh names; the term rhiw, which literally means slope in Welsh, also refers to a well-worn track, usually (part-) constructed on a steep hillside by humans centuries ago, always on a diagonal or series of zig-zag diagonals to ease the steepness. If you’re walking on a rhiw you can be sure that many, many generations have used it before you.

4-way track junction in the autumnal bracken

This rhiw (shown below) has a stone bank built on the downslope side; probably it’s as much an old water-management feature (ditch and bank) to persuade the rainwater down towards a dingle stream, discouraging water from washing freely directly down into fields below.

The rushes growing on the rhiw path/drainage ditch mark an area of water saturation coming down the steep slope then caught by the bank and funnelled diagonally downwards.

Along the ridge top, the Offa’s Dyke long-distance trail is a well-worn track (visible on Google Earth) mostly surfaced with imported gravel or large stone slabs (periodically brought in by helicopter); it’s a popular route and the paving equally benefits both walkers (keeps feet out of bog and wet peat and is a clear path in foggy conditions) and plants because it discourages walkers from creating braided paths by trampling extra bare strips either side of the main pathway.

The hill ponies don’t care about the paths, the Wales/England border or any other lines they cross and recross but they do enjoy embellishing the scenery for admiring walkers.

My favourite line high up on the local common is the Fynnon Line (fynnon = well or spring in Welsh). This is a Black Mountains geological feature where bands of limestone and conglomerate outcrops emerge from the red sandstone and contour round the upper slopes of the steep valleys, the source of many of the hill springs.

The boulders of the fynnon line provide crevices and hidey-holes where trees, bushes and plants can get a hold and grow, protected from the lawn-mowing voraciousness of the sheep’s constant nibbling. It’s a diverse habitat, different from the rough grass, boggy sedges, bilberry and heather which carpet most of the common.

Rowan berries at the fynnon line, early autumn.

This 1922 OS map excerpt (shown below) shows the lack of ‘lines’ on the commons (left half of the image) compared with the many lines shaping fields and farms lower down (right half).

The Wales/England border is clear (dot dash, bottom left corner) as are some footpaths. The band of the fynnon line is represented by the curly, roughly parallel lines that contour within the open common. There are many more streams than those actually marked, some only appearing as temporary white ribbons down the hillside at times of very heavy rain.

Maybe some lines and their impacts on history will be in my mind if I create any artwork for this project………